History

1593

In the spring of 1593, Ottoman forces from the Eyalet of Bosnia laid siege to the city of Sisak in Croatia, starting the Battle of Sisak that eventually ended in a victory for the Christian forces on June 22, 1593. That victory marked the end of the Hundred Years' Croatian-Ottoman War (1493-1593).

The war started on July 29, 1593, when the Ottoman army under Sinan Pasha launched a campaign against the Habsburg Monarchy and captured Győr (Turkish: Yanıkkale) and Komarom (Turkish: Komaron) in 1594.

1594

In early 1594, the Serbs in Banat rose up against the Ottomans. The rebels had, in the character of a holy war, carried war flags with the icon of Saint Sava. The war banners were consecrated by Patriarch Jovan Kantul, and the uprising was aided by Serbian Orthodox metropolitans Rufim Njeguš of Cetinje and Visarion of Trebinje. In response, Ottoman Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha demanded that the green flag of the Prophet Muhammed be brought from Damascus to counter the Serb flag and ordered that the sarcophagus containing the relics of Saint Sava be removed from the Mileševa monastery and transferred to Belgrade via military convoy. Along the way, the Ottoman convoy killed all the people in its path as a warning to the rebels. The Ottomans publicly incinerated the relics of Saint Sava on a pyre atop the Vračar plateau on April 27 and had the ashes scattered.

1595-96

In 1595, an alliance of Christian European powers was organized by Pope Clement VIII to oppose the Ottoman Empire (the Holy League of Pope Clement VIII); a treaty of alliance was signed in Prague by the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II and Sigismund Báthory of Transylvania. Aron Vodă of Moldavia and Michael the Brave of Wallachia joined the alliance later that year. The Spanish Habsburgs sent an army of 6,000 experienced infantry and 2,000 cavalry from the Netherlands under Karl von Mansfeld, commander in chief of the Spanish Army of Flanders, who took the command of the operations in Hungary.

The Ottomans' objective of the war was to seize Vienna, while the Habsburg Monarchy wanted to recapture the central territories of the Kingdom of Hungary controlled by the Ottoman Empire. Control over the Danube line and possession of the fortresses located there was crucial. The war was mainly fought in Royal Hungary (mostly present day western Hungary and southern Slovakia), Transdanubia, Royal Croatia and Slavonia, the Ottoman Empire (Rumelia – present day Bulgaria and Serbia), , and Wallachia (in present-day southern Romania).

In 1595, the Christians, led by Mansfeld, captured Esztergom and Visegrád, strategic fortresses on the Danube, but they did not engage in the siege of the key fortress of Buda. The Ottomans launched a siege of Eger (Turkish: Eğri), conquering it in 1596.

On the Balkans, in 1595 a Spanish fleet of galleys from Naples and Sicily under Pedro de Toledo, marquis of Villafranca, sacked Patras, on the Rumelia Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire, in retaliation for Turkish raids against the Italian coasts. The raid was so spectacular that Sultan Murad III discussed the extermination of the Christians of Constantinople in revenge, but he finally decided to order the expulsion of all the unmarried Greeks from the city. In the following years, Spanish fleets continued to raid the Levant waters, but there was not a reprisal of the large-scale naval warfare between Christians and Ottomans. Instead, they were privateers such as Alonso de Contreras who took the role of harassing the Ottoman sailing.

On the eastern front of the war, Michael the Brave, prince of Wallachia, started a campaign against the Ottomans in the autumn of 1594, conquering several castles near the Lower Danube, including Giurgiu, Brăila, Hârşova, and Silistra, while his Moldavian allies defeated the Ottoman armies in Iaşi and other parts of Moldova. Michael continued his attacks deep within the Ottoman Empire, taking the forts of Nicopolis, Ribnic, and Chilia and even reaching as far as Adrianople. At one point his forces were only 24 kilometres (15 mi) from the Ottoman capital, Constantinople.

He was however forced to fall back across the Danube, and the Ottomans in turn led a massive counter-offensive (100,000 strong) which aimed to not only take back their recently captured possessions but also conquer Wallachia once and for all. The push was initially successful, managing to capture not only Giurgiu but also Bucharest and Târgovişte, in spite of meeting fierce opposition at Călugăreni (23 August 1595). At this point the Ottoman command grew complacent and stopped pursuing the retreating Wallachian army, focusing instead on fortifying Târgovişte and Bucharest and considering their task all but done. Michael had to wait almost two months for aid from his allies to arrive, but when it did his counter-offensive took the Ottomans by surprise, managing to sweep through the Ottoman defences on three successive battlefields, at Târgovişte (18 October), Bucharest (22 October), and Giurgiu (26 October). The Battle of Giurgiu in particular was devastating for the Ottoman forces, which had to retreat across the Danube in disarray.

The war between Wallachia and the Ottomans continued until late 1599, when Michael was unable to continue the war due to poor support from his allies.

The turning point of the war was the Battle of Mezőkeresztes, which took place in the territory of Hungary on October 24–26, 1596. The combined Habsburg-Transylvanian force of 45–50,000 troops was defeated by the Ottoman army. The battle turned when Christian soldiers, thinking they had won the battle, stopped fighting in order to plunder the Ottoman camp. Despite this victory, the Ottomans realized for the first time the superiority of Western military equipment over Ottoman weapons. This battle was the first significant military encounter in Central-Europe between a large Christian army and the Ottoman Turkish Army after the Battle of Mohács. Nevertheless, Austrians recaptured Győr and Komarom in 1598.

The execution of mutinous Walloon mercenaries in 1600. |

|

1601-06

In August 1601, at the Battle of Guruslău, Giorgio Basta and Michael the Brave defeated the Hungarian nobility led by Sigismund Báthory, who accepted Ottoman protection. After the assassination of Michael the Brave by mercenary soldiers under Basta's orders, the Transylvanian nobility, led by Mózes Székely, was again defeated at the Battle of Braşov in 1603 by the Habsburg Empire and Wallachian troops led by Radu Şerban. Hence, the Austrians seemed to be able to win a decisive victory.

The last phase of the war (from 1604 to 1606) corresponds to the uprising of the Prince of Transylvania Stephen Bocskay. When Rudolf – mostly based on false charges – started prosecutions against a number of noble men in order to fill up the court's exhausted treasury, Bocskay, an educated strategist, resisted. He collected desperate Hungarians together with disappointed members of the nobility to start an uprising against the Habsburgs ruler. The troops marched westwards, supported by the Hajduk of Hungary, won some victories and regained the territories that had been lost to the Habsburg army until Bocskay was first declared the Prince of Transylvania (Târgu Mureș, February 21, 1605) and later also to Hungary (Szerencs, April 17, 1605. The Ottoman Empire supported Bocskay with a crown that he refused (being Christian). As Prince of Hungary he accepted negotiations with Rudolf II and concluded the Treaty of Vienna (1606).

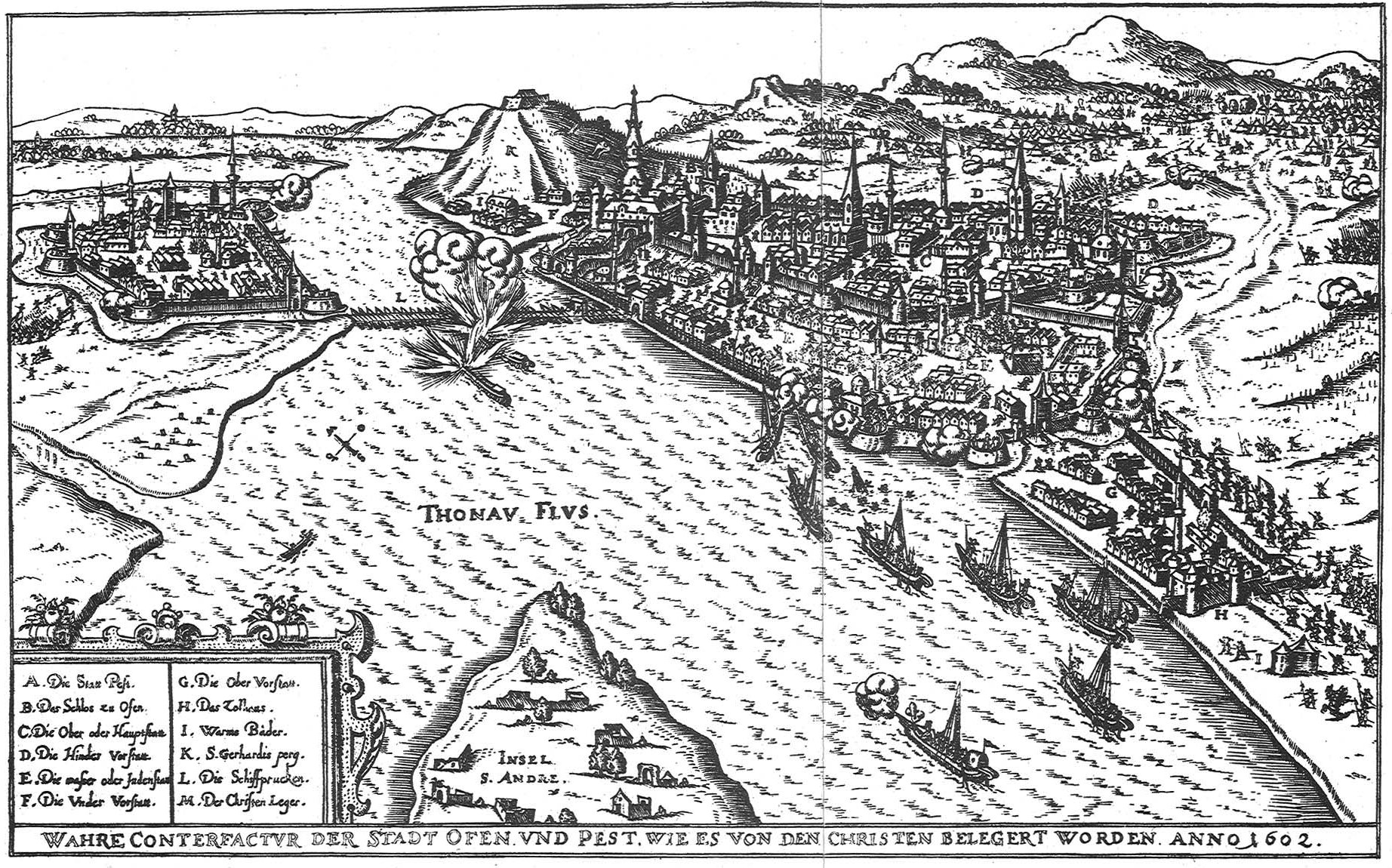

The siege of Buda in 1602. |

|

.jpg)

The siege of Buda. |

|

|